What happens when a person dies of negligence surrounding infrastructure? And how does it complicate matters if they are poor? Families narrate the anguish of crawling inquiries, court runarounds and elusive compensation

Sonu Vangri (centre) lost her sons Arjun and Ankush when the children fell into a barely-covered water tank in the Maharshi Karve Udyan at Wadala on March 17. Pic/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

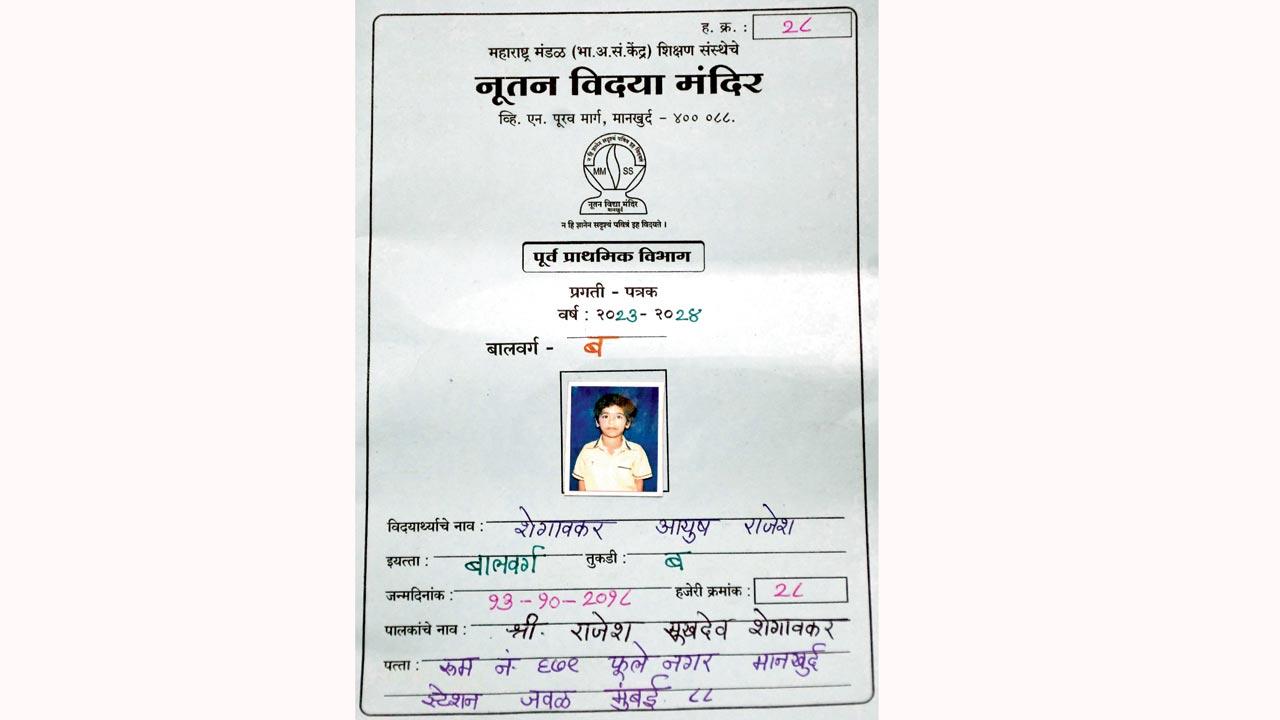

Six-year-old Ayush Shegokar’s favourite activity was play; a rarity in the time of smart screens: Be it pakda-pakdi (catch-and-cook) or just rolling tyres with a stick. Last Sunday (April 22), he ran out of his home in Mankhurd’s Phule Nagar (east) yelling over his shoulder to his grandmother Sulochana that he was going out to play.

At around 10.30 am, neighbours rushed to the Shegokar home saying Ayush had fallen into a pit of water and wasn’t responding to resuscitation. Ayush drowned in a 15-feet pit dug by Mumbai Rail Vikas Corporation (MRVC) for Metro work. “They are children,” says his uncle Vijay Shegokar, “They will wander and play. The authorities should have cordoned off the area, or at least informed us or put up a notice asking us to be careful. How would we know there is a deep pit?”

ADVERTISEMENT

Vijay Shegokar—the paternal uncle of six-year-old Ayush- says that the pit remains open and the entry from Phule Nagar to the railway land where work was undertaken was sealed only on Wednesday. Pics/Ashish Raje

Vijay Shegokar—the paternal uncle of six-year-old Ayush- says that the pit remains open and the entry from Phule Nagar to the railway land where work was undertaken was sealed only on Wednesday. Pics/Ashish Raje

Ayush’s playmate had also fallen into the pit, but he was resuscitated. “We turned Ayush on the side, blew into his mouth, tried to pump his stomach but he just didn’t respond,” Vijay tells us at Mankhurd station. “There was an ambulance parked there, we asked them to help, and they too tried to resuscitate him on the way to the hospital.” Rajawadi Hospital declared Ayush dead on arrival.

It was not the only tragedy to befall the Shegokars.

Sulochna Shegokar, grandmother of Ayush not only lost her grandson but also her son Shailesh, who committed suicide after he couldn’t bare his nephews death

Sulochna Shegokar, grandmother of Ayush not only lost her grandson but also her son Shailesh, who committed suicide after he couldn’t bare his nephews death

As the news spread, family, friends, and neighbhours converged at the hospital. “So did the police,” says Vijay, “They didn’t leave until the next day. They thought we might do something.” The family refused to take Ayush’s body home until those responsible were presented to them. Matter heated further when the police refused to register an FIR. “Finally,” says Vijay, “an officer from the Railways and a journalist family friend intervened, and the case was registered in the evening.”

In this commotion, nobody noticed that Shailesh, Ayush’s uncle, was missing. The 28-year-old considered the talkative six-year-old his son. “At first, we thought he must have tagged along with someone for a ride. He had given his mobile to his elder brother since many people were calling him,” Vijay explains. When he didn’t come home till midnight, Vijay got uneasy. “I went to the Government Railway Police (GRP) and described Shailesh. They requested me to look at the photograph of a man who lay down on the tracks between Chembur and Govandi earlier that evening.”

Ayush Shegokar and Sunil Udasi

Ayush Shegokar and Sunil Udasi

Vijay recognised his cousin’s clothes immediately.

While his family was raging and grieving, Shailesh had sat silently in the corner. “He was completely silent when he heard of Ayush’s death. He just seemed out of it,” says his younger sister Archana. The contractor at Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) was 23 years old when he became Ayush’s proxy father. The one-year-old was handed to his grandmother Sulochana, while his parents did menial jobs in Dadar. “He put Ayush on his shoulders and take him everywhere. If someone assumed he was his son, Shailesh wouldn’t correct them,” says Sulochna when we meet her in a shanty outside Mankhurd station. Rajesh, Ayush’s father, only nods.

Ayush was headed to take admission the day after his death in Standard one. He had scored 89.5 per cent and missed on three days of school

Ayush was headed to take admission the day after his death in Standard one. He had scored 89.5 per cent and missed on three days of school

No one from the police, MRVC, Railways or any other government representative has contacted the Shegokar family. Rajesh was the only one of the three brothers who had a child; and Shailesh was the only stable breadwinner.

No compensation has been offered so far. “Right now we want justice for both our family members,” says Vijay. “Some people are helping us sort out the legalities and hold the Railways responsible.”

Sonu Vangri, the mother of Arjun and Manish who drowned in an open BMC water tank at Wadala says that they hope that the R10 lakh promised by Bombay HC in a suo-moto writ helps to provide a better life for her three remaining children. Pics/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

Sonu Vangri, the mother of Arjun and Manish who drowned in an open BMC water tank at Wadala says that they hope that the R10 lakh promised by Bombay HC in a suo-moto writ helps to provide a better life for her three remaining children. Pics/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

MRVC chief public relations Sunil Udasi said, “The case is under investigation”.

The Vashi Government Railway Police (GRP) registered a case of culpable homicide not amounting to murder under Section 304 of the IPC against the supervisor and the engineer.

The BMC has sealed off the tank in the garden a week after the tragedy

The BMC has sealed off the tank in the garden a week after the tragedy

The area with the fatal pit has been blocked off and warnings pinned on the same; You can no longer access it from Phule Nagar, which is right outside the station. The pit, however, remained uncovered as of Wednesday afternoon. With tin sheets put around it’s perimeter.

It was easy to find Sonu Waghri in Wadala. Shops and thelas have been directing newspersons to her shanty for nearly a month. Surrounded by family, Sonu has been on auto-pilot since her sons—four-year-old Arjun and five-year-old Ankush—drowned at Maharshi Karve Garden nearby. Her youngest child, one-year-old Karan clings to her. She has two elder sons—eight-year-old Mahesh and 10-year-old Manish.

Manoj Vangri says that he hardly understood what was being said during the hearing in Bombay High Court since most of it was in English

Manoj Vangri says that he hardly understood what was being said during the hearing in Bombay High Court since most of it was in English

Her husband, Manoj, sells utensils, clothes. and plastic items on the ferry in Vile Parle. That’s where he was when he got the call about his two sons being missing. “It was Sunday, March 17,” he says.

Arjun and Ankush were joined at the hip. On that fateful Sunday, they took a bath, their mother hand-fed them, and after a quick prayer to the idol in the corner of their shack, they took off with an older cousin. When they didn’t return home by afternoon, Sonu called Manoj to come look for them.

Monika More plays a friendly cricket match after her hand transplant in 2022. File pic/Sameer Markande

Monika More plays a friendly cricket match after her hand transplant in 2022. File pic/Sameer Markande

A shopkeeper at the entrance of the park remembers Manoj running around looking for his sons. Finally, the couple went to Matunga police station to lodge a missing person’s complaint, fearing kidnapping.

On March 18, the police found Ankush and Arjun floating in the water tank right in front of the park’s southern entrance—a two-minute walk from the

Waghri’s shanty. “The post-mortem report said my boys struggled to stay afloat for about an hour before they died,” says Manoj. “They were trapped there, alive.”

Yash Arora

Yash Arora

An FIR for death by accident was filed at RAK Marg Police Station, and BMC, who oversees the park, launched an investigation. While the park belongs to the municipal corporation, the maintenance was leased to a private company named Hiravati Enterprises, which is also responsible for security measures. Shortly, park supervisor Patiram Vikram Yadav was arrested under IPC Section 304 A (culpable homicide).

The CCTV camera of the building across the garden helped locate the boys; Manoj says they could not access the footage from the buildings around their home. The footage showed the children playing near the water tank. While the older boy attempted to fill water from it, the other two fell in.

Gesturing to the thick black tarpaulin covering their home, Manoj says, “They had covered the tank with something like that. And my boys fell in. Now, of course, they’ve covered the tank up.” Police officers confirmed the tanks did not have lids.

“I wasn’t here when it happened,” says the new guard in charge, “I saw them raise the [boundary] walls by at least three feet afterwards.” The BMC has also razed down illegal housing in the area, which includes the Waghri family home.

While the family spoke to us, the other siblings ran around in circles, fascinated by our camera. Manish and Mahesh were eventually pulled in for a family photograph, the first one without their siblings.

What happens when a person dies due to infrastructural oversight? Deputy Municipal Commissioner, Kishor Gandhi, has a straight-forward response: “An inquiry is made. [If] the court rules compensation has to be made, the contractor will do it.” mid-day also reached out to Sachin Varise, Deputy Superintendent of Gardens, but did not receive a response.

In April, the Bombay High Court took the Waghri case up, and filed a suo motu writ petition against the State of Maharashtra.

In the court hearing on April 4, in presence of Judges G S Patel and Kamal Khata, reports by the Wadala Citizen forum were brought up. The residents had repeatedly complained about uncovered tanks, but the BMC had said they faced “budgetary constraints”. The article referenced, written by Jyoti Punwani, posed an arresting question: Is there any justification for failure to provide minimum safety measures in civic body-operated structures?

In the subsequent hearing on April 23, senior advocate Anil Singh, on behalf of the BMC, stated there was a provision for ad hoc compensation to be paid by the contractor. Manoj does not have a bank account, but his uncle does. The money is to be credited to the Suo Motu Writ Petition, Sharan Jagtiani, senior advocate, is to coordinate with the family for the withdrawal of the money.

“We went to the High Court near VT, and the judge said he’ll give us our compensation. I took my uncle with me.” Manoj told us. He took the train, got off at CSMT, took a cab to court, and listened intently to the hearing of which he understood little to none. No one in the Waghri family understands English.

“It’s not like I can speak in court,” Manoj said. He just stood there. He didn’t know the judge’s name, or the council’s name who assured him that he will be given the Rs 10 lakh promised by BMC. What did he think about during those hours? The face of his children who loved to go to school? The home he had built after living in perpetual poverty? His sister who had passed away just months before his children? A wife tormented by grief just like him?

What happens if he is not given what he has been promised? “The judge will ensure it gets done. He said so.” Manoj replies with faith. We’re not sure if he believed what he just said. We’re not sure if he has any other choice.

There are several other legal proceedings of the infrastructural mishaps that involve the victim and the BMC, Railways, Metro, or a government official.

For instance, a 15-year-old boy in Chembur was fatally electrocuted by a metal sheet used to block the road for metro construction. Investigation revealed that the iron sheets had lights on them and one of the wires was exposed, making the sheets electrically active. The construction was near a residential area. An FIR was filed against the MMRDA supervisor and two workers were arrested for negligence.

Like Manoj, many can’t pursue justice mainly because they didn’t understand the jargon or afford a better lawyer. Very few know about the free legal aid they are entitled to through Maharashtra State Legal Services Authority under the Legal Services Authority Act, 1987. The is not applicable for cases against a private entity.

“All underprivileged persons affected by a civic or government body,” says advocate Yash Arora, “can approach the Bombay High Court for Legal Aid Redressal Forum.

It’s on the first floor of the PWD building in High Court.” The High Court designated panel has advocates specialising in different areas, and depending on the victim’s grievance, a lawyer is assigned. “The lawyers’ fees are paid by the State of Maharashtra,” says Adv Arora. “ However, more awareness should be created about these legal facilities by the Court’s Tribunal and the state.” Legal aid lawyers mostly work against criminal offences, but include civil cases if the problem is against a human body or governed body, and involves a compensation fee.

The biggest challenge for those from economically weak sections of society is the language barrier. Legal proceedings in the High Court are conducted in English. The responsibility to simplify legalese often falls on the lawyers.

There are some happy—relatively—endings. In 2012, 16-year-old Monika More fell off a running train at Ghatkopar as the gap between the footboard and the train was unusually wide. More lost both her arms from elbow downwards.

Months of allegations and counter-allegations between the More family and the Railways ensued. While the family blamed the gap, the Railways countered that since More was travelling on the footboard, it disqualified her from compensation.

In 2022, More underwent a hand transplant surgery and is bubbly over the phone. “I am doing well,” she says. “I work as a patient care provider in Gleneagles Hospitals Parel where my surgery took place.” More now instils hope with victims of trauma and accidents. “I try to help people in whatever way I can,” she says. “I don’t remember much from the accident or the months after, but I know my father fought for me. I would just like to say this: Don’t lose hope. Keep going forward.”

— Inputs by Tanya Syed and Sanjeevni Iyer

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!